7 Chapter Seven: Gougane Barra

Gougane Barra

The sun is a suggestion. It slips in

where it can – some light-

charmed stream. A waterfall,

water lacing down through rocks.

We’ve hiked along a maze

of beech and aspen, up to where

beards of bog moss grow thick

on boulders – darked to browns

in shade. Here ferns hold firm,

their tongueroots mining cracks into

the greening stones. Just off the path,

blue-line veining, orange crowns –

the mapwork inch-round mushrooms

know. Wonders more ahead- the moor –

til we find us

turned, gone all ways.

We are urged on,

along old confusions

never settled. Like those spare hills

shadowed below,

of distance this is:

the mist that pauses

now, shapeless,

then sures

to the thinness of air.

– Gougane Barra Forest Park, Ireland

Steve Wilson

The Midwest Quarterly; Spring 2009; 50, 3; ProQuest

pg. 259

Entry #1: “In spite of twenty centuries of Christianity, the old pagan practices at healing wells have survived–a striking instance of human conservatism. St. Patrick found the pagans of his day worshipping a well called Slán, ‘health-giving,’ and offering sacrifices to it, and the Irish peasant to-day has no doubt that there is something divine about his holy wells. The Celts brought the belief in the divinity of springs and wells with them, but would naturally adopt local cults wherever they found them. Afterwards the Church placed the old pagan wells under the protection of saints, but part of the ritual often remained unchanged. . . . The patient perambulated the well three times deiseil or sun-wise, taking care not to utter a word. Then he knelt at the well and prayed to the divinity for his healing. Then he drank of the waters, bathed in them, or laved his limbs or sores, probably attended by the priestess of the well. Having paid his dues, he made an offering to the divinity of the well, and affixed the bandage or part of his clothing to the well or a tree near by” (MacCulloch 193-4).

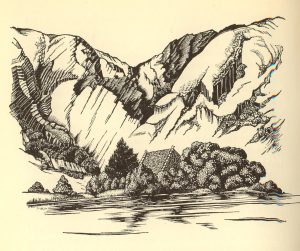

Entry #2: Gougane

Barra (Finbarr’s Cleft) Signed south of Macroom on the R584, 4.5 miles past Ballingeary. The site has been a forest park since 1966.

The Lee Valley is strongly associated with the early life of St. Finbarr. His father’s land was outside Macroom and it was here at Macloneigh that he founded his first church. He is the Patrick of Munster bringing Christianity to the southwest and, like Patrick, he is depicted with crozier and mitre, a patriarchal and political figure in church history. He is officially remembered as the founder of Cork city and its first bishop, but he is probably most popularly associated with his hermitage and oratory here at Gougane Barra, the source of the River Lee.

His pattern replaces the old midsummer gathering here at this very powerful nature site at the source of the river. In times past, cattle were driven through the water here to ensure their health and well-being for the coming year. The island, which is joined by a causeway, had a wooden pole erected at the centre where votive rags and spaneels of cattle were hung. Part of the lake was enclosed and treated as a holy well for bathing. This was often the only bathing of the year and was considered to ensure good health for the whole year. Unlike at other times, there was no danger of drowning during the midsummer bathing. (Sacred Ireland)

Entry #3:  “Wouldn’t you be frightened?” asked Mickey Tobin when, during the evening of 23rd June, I mentioned to him that I was going to sleep on the lake that night. “I wouldn’t do it for a thousand pounds,” he said.

“Wouldn’t you be frightened?” asked Mickey Tobin when, during the evening of 23rd June, I mentioned to him that I was going to sleep on the lake that night. “I wouldn’t do it for a thousand pounds,” he said.

“Why not,” I asked.

“It’s Midsummer Night,” he said.

“I have the hazel stick you gave me,” I told him.

“I’d be frightened all the same,” he said.

The easterly wind had faded when I reached the head of the lake. Momentarily a light breeze ruffled the surface of the water; then it too died away and again there was calm and peace.

There was no darkness that night, just a twilight as the sun took its course to the north, a twilight pierced by the light of fires that blazed on successive hills. From where I lay in my boat I could see on a knoll behind the island figures dancing around a bonfire, and I could hear the music of the fiddles that accompanied them. Then, as the blaze subsided, I saw men, women, and children leaping through the flames, and trails of sparks like comets, as live brands were plucked from the fire and thrown into the air. I remembered how, many years ago, when the people of Knockainy neglected to light the usual Midsummer fires on the Hill of Aine, a fairy princess, they were surprised and alarmed to see the hill ablaze with fires through the night.

And while I watched these people celebrating, unconsciously, a pagan rite, I knew that other celebrants were moving on the dark island, this time worshipping in the Christian faith—pilgrims to the shrine of St. Finnbarr, to the cells where he and his monks prayed and fasted twelve centuries ago. Each pilgrim makes a round of the “stations” before midnight; five prayers at the first cell, ten at the second, fifteen at the third, until at the ninth and last they say forty-five. Further prayers are said at the holy well. Two hours it takes them, and the series must be completed before midnight. Some of the worshippers stay on to do another round after midnight, others keep vigil till the dawn.

. . . .

When I awoke in the boat before dawn, the crescent moon was tipping the low hill to the east. Soon it was lost in the glory of the rising sun. The morning was warm so I slipped into the lake; then for a while I rejoiced in the cool sunshine.

It was still early when I tied up my boat by the hotel. Mick Tobin was waiting for me.

“Are you all right?” he asked.

“I’m grand,” I said.

“I’ve a drop for you here,” he said, handing me a glass of whiskey. “I thought you might be wanting something. Do you know,” he added, “Teigue the Pass was for taking his fiddle along the mountains last night and playing to you from above. He said you’d be thinking ‘twas fairy music. But the boys wouldn’t let him. They said you might do something desperate from the fright that would be on you.” (Sweet Cork of Thee by Robert Gibbings, 1951).

Entry #4: “Soon after I reached Gougane, an old friend of mine, Tim Leahy, a farmer, told me that he had to go to Killarney. . . . So we started off in his car, east through Ballingeary and then north up a steep valley with rugged hills on either side and the Bunsheelin Rive rumbling through its boulder-strewn course towards us. From there, across the saddle of the mountain, with the Paps of Dana, far to the north, dominating a nearer range of hills. These twin mountains take their name from Dana mother of the Irish gods who in pagan times were worshipped in Munster as the goddess of plenty. According to bardic chroniclers, the Tuatha De Danaan, the People of the Goddess Dana, on being conquested by the Milesians centuries before the Christian era, held council among themselves and decided henceforth to live underground in the hills. There they built palaces for themselves, resplendent with gold and precious stones, and there according to some people they still live, being known to-day as shee or fairies” (Gibbons Sweet Cork of Thee 12).