Livonian

HISTORY

Ancient history

The ancestors of the Livonians and Latvians, the Finnic and Baltic tribes, arrived the territory of present-day Latvia in the Late Bronze Age. By the 12th century, the Livonian nation had come into existence and later merged with the ancient Baltic nations of Latvia – the Latgalians, Curonians, Semigallians, and Selonians – forming the Latvian nation. The development of the Livonian area can be observed from the 10th century, but more reliable data is from the 12th century when the Livonians occur in historical records. The Livonians are first mentioned in “Повесть временных лет” (Tale of bygone years), written by the monk Nestor of the Pechersk Monastery in Kyiv. In that record, the Livonians are mentioned in the form либь ~ любь. Livonian culture flourished in the 11th and 12th centuries.

More detailed information about the Livonians of Vidzeme from the late 12th and early 13th centuries is found in the Livonian Chronicle of Henry where Livonians and their territories are mentioned as of the 1180s. This chronicle records the conquest and conversion to Christianity of the Baltic and Livonian lands by the Germans and Teutonic Knights. It is mainly from this chronicle that we have knowledge of the ancient Livonian tribes, their social organization, customs, religion, and territories. The events of the late 13th century were recorded in the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle where its author says the following about the Livonians: “There by the River Daugava (Dune), which flows here from Russia (Ruzen), there lived a godless people, very brave in battle: – the Livonians (Liwen) – so they were called.” In the 13th century, other sources also mention the Livonians: contracts, documents, and descriptions of their customary law. At this time the Livonians can be considered an ethnicity with its own identity, as they are treated as a separate group in written sources.

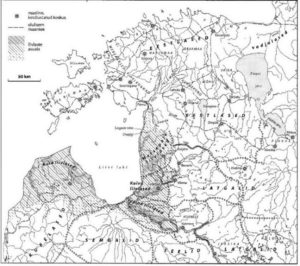

Based on archaeological and written sources, two large regions can be identified in Latvia at the end of the 12th century as having been inhabited by the Livonians: northern Courland (Kurzeme) and Vidzeme, which includes the Lower Daugava, the Lower Gauja, Metsepole, and Idumea (see Figure 4).

Nowadays it is no longer possible to say with certainty what was the source of the name of the Livonian people or what its original form was in Livonian. The Latin livones used in the Livonian Chronicle of Henry and the German Liven was most likely borrowed from a term already used for the Livonians in Scandinavia and later borrowed from German into other languages including Estonian and Modern Russian. In ancient Russian sources, the Livonians are referred to by name in the 11th century (либь ~ любь) and this corresponds to the term lībieši used by the Livonians’ closest neighbors – the Latvians – which is first attested in the 14th century. The Livonians also referred to themselves as līb roust (in Vidzeme) or rāndalizt (in Kurzeme). Modern Livonian uses the term līvlizt, which was borrowed from Estonian in the 1920s.

The Livonians up to the 20th century

In the early 14th century, the Vidzeme Livonians gradually began to assimilate into the Latgalians and other Baltic tribes of Latvia laying the foundation for the development of the Latvian language and people. It appears that Livonian was spoken in the Daugava and Idumea regions until the 15th-16th centuries, in the Gauja region until the 17th century, but in the Metsepole region up until the mid-19th century.

Less is known about the Courland Livonians. Written records and linguistic evidence show that the Courland Livonians lived mixed with the Curonians, who ruled over most of historic Courland in the 12th-13th centuries. The Courland Livonians are also associated with the Vends, who at some time in the past moved from the Lower Venta to Rīga and were living in Cēsis by the 12th century.

It is known that in the 16th-17th centuries, Livonian was spoken in northern Courland. At that time the Livonians began to adopt Latvian, which had already developed as a language in Vidzeme, and the area they inhabited began to shrink. Over the centuries, the number of Livonians in Courland and Vidzeme decreased, accompanied by a language shift. In Vidzeme, this process came to an end in the 1860s. The last speaker of Vidzeme Livonian died in 1868. Salaca Livonian is the only form of Livonian spoken on the territory of historical Livonia. In the second half of the 18th and early 19th centuries, the Livonians lived as a homogeneous ethnic group only from Ovīši to Ģipka.

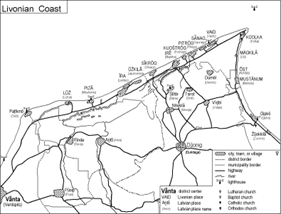

By the early 20th century Livonian was only spoken in the fishing villages in northern Courland, known today as the Livonian Coast (Figure 5). Traditionally, Courland Livonian has been divided into East (spoken in the villages of Ūžkilā (Latvian Jaunciems), Sīkrõg (Sīkrags), Irē (Mazirbe), Kuoštrõg (Košrags), Pitrõg (Pitrags), Sǟnag (Saunags), Vaid (Vaide), Kūolka (Kolka), Mägkilā (Uši), Ōst (Aizklāņi), Mustānum (Melnsils)) and West Livonian (the villages Paţikmǭ (Latvian Oviši), Lūž (Lūžņa), Pizā (Miķeļtornis), Īra (Lielirbe)) dialects. Livonian spoken in the village of Īra on the banks of the Īra River has also sometimes been considered a central dialect or a transition area between western and eastern Livonian.

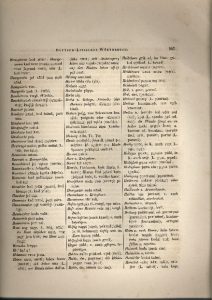

The 19th century is noteworthy for being the period when scientific research into the Livonians began. Major collection work of Livonian linguistic data began in the middle of the 19th century with the publication of the first important collection of Livonian – a Livonian-German and German-Livonian dictionary (Sjögren & Wiedemann 1861a, see an example of the page in Figure 6) and a grammar with language examples (Sjögren & Wiedemann 1861b) by Finnish scholar Andreas Johan Sjögren and Estonian scholar Ferdinand Johann Wiedemann, who collected data during their expeditions in 1846, 1852, and 1858 under assignment from the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences.

The Gospel of Matthew was published in the Eastern and Western dialects of Courland Livonian in London in 1863, the first known work published in Livonian. Both books were published as a single volume in St. Petersburg in 1880 and this became the first Livonian publication to reach the Livonians themselves.

Between the two Worlds Wars

World War I forced the Livonians into exile and sent them further inland in Latvia and to Estonia and Russia. It also accelerated the decline in their numbers as well as their linguistic assimilation. Of the Livonian-inhabited villages in northern Courland, Irē (Latvian Mazirbe) became the most important center of the community and cultural life due to its location and active economy. In Irē there was a church, school, post office, clinic with a doctor and midwife, pharmacy, teahouse, barber shop, photographer’s studio, steam mill, sawmill, fish smokehouse, brick kiln, several stores, and the fishing cooperative “Zivs” (Fish). During World War I, the narrow-gauge railway was built and called piški bōņ in Livonian (‘a little train’). The train came from Vǟnta (Latvian Ventspils) and turned at Irē towards Dūoņig (Dundaga) and Stēņḑa (Stende). In the 1920s and 1930s, seven primary schools were operating in the Livonian villages.

With the end of World War I and the establishment of the Republic of Latvia in 1918, the stage was set for a dramatic improvement in the conditions and use of the Livonian language in its traditional home on the northern coast of Courland. The towns were somewhat isolated from the rest of Courland by a belt of uninhabited forests and swamps, which allowed the Livonian identity of the area to be preserved. However, the situation of the Livonians was not easy in the 1920s: World War I as a result of the exile, the younger generation of Livonians partially lost their language, the Livonian language was not used in schools or churches, there were no native speakers reading material, general poverty prevailed in Livonian villages.

In the early 1920s, a new generation of linguists began arriving on the Livonian Coast. The two most notable researchers were Finnish linguist Lauri Kettunen (1885–1963) and Estonian folklorist Oskar Loorits (1900–1961). Livonians were encouraged to take pride in their language and culture. Oskar Loorits actively contributed to Livonian community actions. His extensive documentation of Livonian is of great value to researchers. He focused on investigating Livonian folklore and defended his doctoral dissertation in 1926 on Livonian folk religion.

To strengthen the position of Livonian, Estonian activists published five Livonian readers (in 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, and 1926). The Livonian books published in the 1930s were generally of a religious nature. The first newspaper in Livonian – “Līvli” (The Livonian) – was published in Jelgava in 1931. It was published monthly until August 1939.

The interwar period was productive for Livonian cultural life and had relatively positive conditions for language development. Following Latvia’s independence declaration in 1918, the Livonian community and cultural life also became more organized. The largest and oldest Livonian community organization, the Livonian Union (Līvõd Īt) was established on April 2, 1923, in Irē. The following goals were listed in its statutes: to keep the Livonian language alive, to spread knowledge and learning among the Livonians, and to help improve their economic and social life. The Livonian choirs were an important part of cultural life. The first Livonian Union choir was organized in 1922. On June 24, 1924, the first Livonian Song Festival took place.

With the assistance of the Finnish Awakening Society (Herättäjä- yhdistys), for the first time it was possible for the Livonians also to attend religious services in their own language. Several times a year the Finnish pastor would travel to the Livonian villages thanks to financial support from the Awakening Society, and hold services, baptize children, conduct funerals, and even organize confirmation and Sunday school classes. The first known service in Livonian occurred in the Irē Church in January 1931. Due to its location, Irē became the major Livonian center in the 1920s and 1930s. It also received significant financial assistance from Estonia, Finland, and Hungary for constructing the Livonian National House, which was opened in Irē on August 6, 1939.

Soviet period

After World War II, the number of Livonians quickly decreased. The reasons for this included emigration, deportation, fear of advertising one’s ethnic affiliation, and the frequent unwillingness of Soviet officials to accept the ethnicity “Livonian” for official purposes.

In the 1940s, the Livonian-inhabited Baltic Sea and Gulf of Rīga coasts were declared the western border zone of the former USSR. Many border guard posts and military units were placed in and around the Livonian villages. Coastal fishing was gradually eliminated in the smaller villages and concentrated in the larger population centers of Kūolka, Roja, and Ventspils. Limits were placed on freedom of movement for inhabitants. This forced working-age people to look for work elsewhere, emptying the villages. Some buildings were sold by the Livonians to summer holidaymakers, some stayed in families, and others collapsed.

During the Soviet period, the Livonian community and cultural life only became active in the 1970s. This is due to several actions, one of which was the establishment of the Livonian ethnographic ensembles Līvlist in Rīga and Kāndla in Ventspils. These were established to preserve and develop the Livonian language and musical heritage. Livonian songs were also popularized by the folklore group Skandinieki. In the 1970s, several significant events for Livonian cultural life took place, e.g., the placement of a memorial stone honoring Livonian poets at the Pizā (Latvian Miķeļtornis) cemetery during the Poetry Days in September 1978 and an exhibit of Livonian ethnographic objects entitled Rāndali (Coast dweller).

In August 1978, members of the Livonian and Latvian intelligentsia asked the leadership of the Latvian SSR to recognize the Livonians as a separate ethnicity and work to prevent their assimilation. This request, however, had no official positive results.

Livonian in the 21st century

In the current century, there have been remarkable developments affecting Livonian. Various actions are initiated to promote the Livonian language and culture. For example, the International Year of Livonian Language and Culture in 2011 noticeably invigorated the discussion of Livonian-related questions within Latvia and abroad (see the logo in Figure 7). The discussions involved the status of Livonian in Latvia, the social setting for its use, and the ways in which it is used in everyday life. There are difficulties associated with Livonian language acquisition and language development as well as a description of Livonian language pedagogical materials and other resources, which have been recently developed or are in the process of being developed. However, methods and opportunities for further developing Livonian and improving its current situation are discussed in the context of potential solutions and already existing initiatives.

A relatively new trend can also be observed in that websites and social networks are being used more actively to popularize the Livonians and the Livonian language and share information related to these topics. With respect to intensive Livonian language study, a successful example can be mentioned. Already since 1992, the Livonian children’s summer camp Mierlinkizt has taken place every summer. Children from around Latvia learn the Livonian language at the camp for several weeks.

Even if it is not possible to learn a great deal about Livonian during such a short time and even if a majority of the camp participants do not come into contact with Livonian in the interim, this camp is the first exposure for a large number of the camp participants to Livonian (which for many of them is their family’s heritage language) and potentially can prompt them to further efforts in studying Livonian. Since 1989, Livonian celebrations have been organized on the first Saturday of August on the Livonian beach in Mazirbe in honor of the Livonian Community House. During the celebration, concerts and performances take place, exhibitions are opened, lectures are held, and dancing is held.

Despite only a handful of speakers, the Livonian community in Latvia is active in preserving and developing the Livonian heritage and language plays a key role in this process. In 2018, the first scientific Livonian center was founded – the Livonian Institute at the University of Latvia. The head of the institute Valts Ernštreits looks positively to the future: „ Motivation is important: there must be no feeling that the Livonian stuff is just the stuff of the past. It is not just a Livonian heritage, it is a living culture! And for it to be a living culture, it must function as a living culture. We must not focus too much on what has been but constantly look to the future. Otherwise, there is a risk of canning and drying out.“ (Newspaper Sirp 19.06.2020)

In order to motivate the regions historically inhabited by the Livonians to study and highlight their Livonian roots, to discover and display Livonian elements in their region’s landscape, events, and everyday life, the University of Latvia Livonian Institute in cooperation with the Latvian National Commission for UNESCO and the Latvian National Centre for Culture has declared 2023 to be the Year of Livonian Heritage (see logos on Figure 8).

Figure 8. Official logos of the Livonian Heritage Year in Livonian, Latvian and Estonian (author: Zane Ernštreite).

On the first Sunday after the Spring Equinox, which in 2023 fell on March 26th, Livonian Heritage Day was celebrated for the first time in the regions historically inhabited by the Livonians. On that day regions decorated local places of significance especially those associated with the Livonians with Livonian green-white-blue flags or colors. Likewise, people participated in the Livonian spring bird waking ritual, the roots of which are found in antiquity and which took place in many locations across Latvia. Bird waking is an ancient tradition specifically characteristic of the Livonians. It is associated with the Finnic (Livonian, Estonian, Finnish, Karelian, etc.) mythical view that the world arose from the egg of a water bird. Bird waking, which marks the beginning of the year for the Livonians and the reawakening of all life, is an echo of this ancient myth. The Livonian myth is grounded in the traditional view that migratory birds do not leave in the fall but spend the winter at the bottom or along the shore of the sea, rivers, or lakes, and that in the spring they have to be awoken.

Media Attributions

- Picture6

- Picture7

- Picture8

- Picture9

- Picture10

- Picture11

- Picture12

- Picture13

- Picture14

- Picture15

- Picture16

- Picture17

- Picture18

- Picture19

- Picture20

- Picture21