Mwaghavul (Sura)

INTRODUCTION

Why is this considered a minority/ized language or culture?

Mwaghavul is both the name of the language (glossonym) and the people who speak it (ethnonym). Ethnologue (2000) 14th Eition listed the number of speakers of Mwaghavul to be 295.000 referencing (1993 SIL) The 2022, 25th Edition gave the number of speakers as 150,000 (attributed to Roger Blench, 2016), Blench 2020 informal estimate is 200,000, while the Joshua Project (parochial research initiative with missionary agenda) listed 175,000 as the population of the Mwaghavul. These figures make Mwaghavul a minority people with a minority and seemingly endangered language.

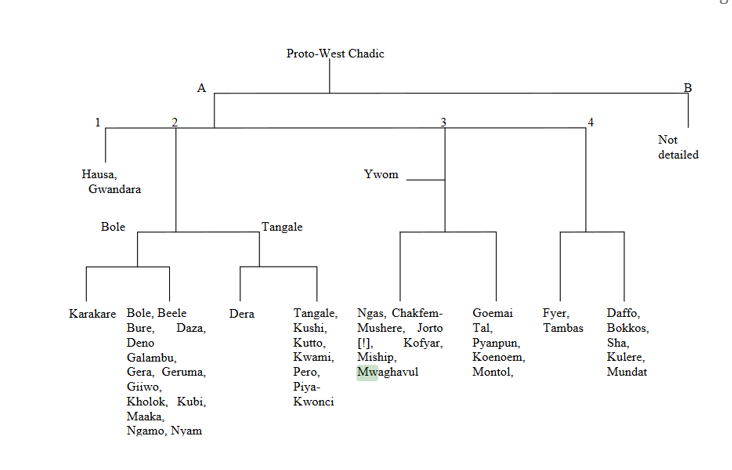

Located in the North-Central East of Nigeria, Mwaghavul is one of the 150 Chadic languages belonging to the Afro-Asiatic phylla. The Chadic family is divided into 4 major branches: West, Central, East, and West. West Chadic has about 70-77 languages, and it is further subdivided into two main branches A and B. The A subbranch is further divided into 4 sub-branches: A1, A2, A3 and A4. Mwaghavul along with Ngas and Kofyar languages fall under West Chadic A3.

The location of Mwaghavul in the Classification of West Chadic language (Blench 2020: xviii)

Archaeological findings reveal significant human presence in the current location of the Mwaghavul since the paleolithic age. More pronounced is the Nok civilization of the Berom, neighbors of the Mwaghavul. Due to the scant scholarship on the people, linguistic and cultural evidence presumed a probable migration of the people from the Chad Basin. They left fleeing internecine of the Bornu Empire ca 1100 BCE and 1350 CE as well as the slowly desiccating Lake Chad on which they and many other groups have depended for water and marine life. Of special note are the wars associated with the state formation of the Kanem-Borno and Hausaland and the military and religious efforts of these emerging kingdoms to forcefully subordinate and incorporate the Mwaghavul and other groups of the region into their system of centralized government. Up to the contemporary times, the Mwaghavul among others continue resisting not only the political domination of the Kanem-Bornu, but also the pressure to accept Islam just as they did during the Fulani Jihad in the early part of the 19th century. The Mwaghavul were not alone in their exodus from the Chad basin, fleeing with them were other peoples of northern Nigeria such as the Ngas, Mupun, Chip, Takas, and Kofyar among others. They are all classified as also belonging to the West Chadic A3 linguistic group. While the Mwaghavul continued until their present location in the Jos-plateau, some of these other people separated and settled in different regions of the plateau. This their common origin accounts for the commonalities found in their languages and cultural practices. Linguistic comparisons affirm this affinity such that Mupun and Mwaghavul, for instance, are considered dialects of a language, that is, they are mutually intelligible with only minor lexical and phonetic differences between them. Their perception of social, political, and geographical differences between them significantly influences how they perceive any linguistic differences (Frajzyngier,1991). Ngas and Mwaghavul are also dialects of a language, nevertheless, despite their geographical proximity and linguistic similarities, mutual intelligibility does not readily exist, and where attested, it is often uni-dimensional and not reciprocal, although their affinity is attested in other areas such as customs, traditions, and religious practices.

The Mwaghavul settled down in the Jos-plateau area, where the rocky hills and caves of the plateau provide them a natural refuge and economic resources. The topographical features of this area have, over time, stood them in good stead, offering them protection against enemies’ attacks and strategic advantages in military encounters. Their possession and use of ponies and horses also added to their advantage in warding off the menacing Hausas, as well as assisted them to successfully carry out raids against the nomadic Fulani pastoralists, and win wars against their other neighbors (Lohor, 2012). The plateau is a source of many water bodies that nourish the people, and its mineral deposits enrich the soil. Mwaghavul people exploit the fertile and arable land of the Jos-plateau for agricultural purposes and thus led a sendentary life of farming and hunting.

While some oral history claims autochthonous existence for some groups and the migration of others, the Jos-plateau region is home to a confluence of 3 language phyla (a group of language that stem from a common ancestral language), tens of undocumented languages, and multiple dialects of each. It would seem that both the migrating peoples and the autochthonous ones intermixed to form the current people and culture called the Mwaghavul within a locality of the same name, and separate from their Benue-Congo neighbors, and the more dominant Hausa and Fulani speakers. It has been suggested that the ethnonym is probably a federal name that subsumes previously autonomous groups within Mwaghavul land, which became cemented when the collective united to resist initial missionary activities and colonial incursions.

Known in older writings as Sura, Mwaghavul and neighboring peoples, now indigenous to the area, form an island of West Chadic A3 languages and cultures. They are bounded by the most prominent member of the West Chadic A1 family, Hausa, listed as having 55, 800,000 users in Nigeria; the Kanuri, who, with 8, 150,000 speakers are the largest Nilo-Saharan language family of the Chad Basin, and some languages of the Kwa and Bantu sub-groups of the Benue-Congo language family such as Bache, Anaguta, Irigwe, Berom, Pyem and Tarok. Blench (2020) noted for the Jos-Plateau area that “for many centuries, three of the four African language family phyla: Afro-Asiatic, Niger-Congo and Nilo- Saharan have converged, overlapped and interacted in the area.”

Linguistic and cultural viability:

A network of social and economic factors has contributed to the gradual abandonment of Mwaghavul for other linguistic resources not offered by their own language as shown in the following section.

Imposed on by English, the colonial language of administration, and dominating Hausa neighbors who are the largest speakers of Chadic language in Nigeria, Mwaghavul language struggles for vitality. The imperialism of these languages -foreign and domestic-which are (a) written, (b) the medium of instructions in formal education, news, and entertainments, and (c) along with the attributed social capital that influenced their being perceived as, and associated with, urbanism and modernity have contributed to the diminishing minority status of Mwaghavul and exacerbated its declining prestige. For instance, lacking official status, Mwaghavul is a subordinated language, most of its speakers are functionally trilingual. They speak as their mother tongue Mwaghavul, Hausa as the lingua Franca, and English as the national language of education and literacy. Owing to the location of the people, encircled by majority languages and English, the language is viewed by its speakers’ and the state’s as lacking power, socio-economic capital, and prestige.

Vitality: With respect to its linguistic vitality (Giles et al., 1977) Mwaghavul is not a language of education, government, Churches, or media, it is primarily a home language. In his dedication to the Mwaghavul-English dictionary, Daapya, one of the contributors, suggested for retention and continuity the language: “We should go back to the practice of at least singing one

song in the Mwaghavul hymnbook each Sunday and our children would be forced to read and write Mwaghavul language” (Blench et al, 2012: iv). As will be shown below, the native speakers would appear to preference English and Hausa languages even for religious activities, only about 10% of the population are said to still speak it actively at home. These speakers wield little political or economic power either within the state of their location or in the country-Nigeria in general. In fact, the dictionary is aimed, according to the authors, “specifically for those children who are products of inter-tribal marriages and those who grew up outside Mwaghavul chiefdom and therefore are deprived of the normal experience and socialisation process in Mwaghavul culture. I have decided to be more explicit in my definitions to give background information, considering the fact that they have been detached from the community, so to say” (Blench et al, 2012: iv), and also out of concern that the language will die a natural death.

Education: there are state-run primary and secondary schools within the local government’s areas of Mangu and Panyam. However, the language of education is not Mwaghavul. In elementary school, early children education begins in Hausa with English taught as a subject; after the lower elementary classes, the language of instruction gradually transitions to English, but not exclusively. Often, there is switching of codes between English and Hausa. In secondary (high) school, pupils are expected to have gained sufficient knowledge of English for it to be the dominant language of instruction, supported by Hausa, both of which are also subjects in the curriculum. There is across board multilingualism especially among younger people, the majority of whom shift to using other languages to meet those social affordances absent for their native language. This language shift has implicated literary in Mwaghavul. L1 literacy rate in Mwaghavul is slated as 10-30%, while it is 50-70% for L2 (Ethnologue, 2022), which in this case, are Hausa and English. As a result, there is no institutional support for Mwaghavul, the language does not play any important role in literacy. Some of the consequences of the displacement of Mwaghavul includes a lack of curriculum in the language, and a gradual and continuous replacement of it by these other languages as the primary languages of socialization and communication, consequently, the culture and values of these other languages assume dominance. Currently, most vestigial L1 speakers of Mwaghavul are older population that are mostly engaged in traditional subsistence economy.

Orthography: Documentation of Mwaghavul language is still at best at its most initial stages. Without indigenous script, European missionaries developed the first popularized writing system adapted from Yoruba orthography at the beginning of the 1900s. Initial linguistic description of Mwaghavul owes to Herrmann Jungraithmayr’s 1963 work, titled Die Sprache der Sura (Maghavul) in Nordnigerien. Published in German, it contained a German-Sura (Mwaghavul) dictionary and a linguistic description of the language. Prior works that explore the language was often in association with related dialects e.g., Mupun and Ngas. The first English-Mwaghavul dictionary based on electronic manuscript prepared by Daapyaa (2007) was initiated by Blench in collaboration with some members of the Bible translators. Published in 2021, it remains the only dictionary of the language. Revision to the existing orthography was made by Nyang and colleagues in 2019 while Blench and Dawum produced a grammar in 2019.

Scholarship: Perhaps the first publication in Mwaghavul language was Edward Hayward’s (1920) translation of the first eleven chapters of the first book of the Bible, entitled Genesis in Sura (Mwaghavul). Other portions of the scripture were to follow; these include Old Testament stories (1927); Catechism (1915), Hymns and prayer titled kwop naan shi kook mo (1981), and the New Testament (1992). These activities due to the Church Missionary Society, the Joshua Project, SIL and other religious entities are crucial in the documentation of the language. Scholarly academic work on Mwaghavul began in 1920s. A comparative word list of Mwaghavul (sura) as part of the study of Chadic languages appeared in 1975 and 1981. Eager field-work researchers associated with the Kay Williams Educational Foundation have championed the study of minority languages in Jos-Plateau area including Mwaghavul. Specific mention should be made of Roger Blench who has studied its expressives (2013), its nasal prefix particle, pluractional verbs (2011), and its disease names (2013)[1], among other publications. Scholars in the departments of linguistics and History at the University of Jos are also contributing works explicating the peoples and their cultures and providing contemporary understanding of their history, politics, life, and practices. Some of these include study of its Idioms, bride price and women; Mwaghavul religion (Danfulani, 1997; Frank 1997; Danfulani 2021), ritual dance (Danfulani 1996), folktales (Longdet 2015), agriculture (Lohor 1993; Gubam 2021), and history and culture (Danfulani 2003; Hyeland et al 2014). A careful bibliography on Mwaghavul will show not more than 100 published works overall.

Subsistence: Established in the Jos-Plateau, where the climate is very mild with abundant rainfall that sources many rivers, spring waters and lakes, the Mwaghavul are renowned farmers and hunters, together with their neighbors, they form the breadbasket of the middle-belt of Nigeria. Their staple food includes millet, sorghum, root crops, especially potatoes, supplementarily, they keep domesticated animals. They are also engaged in tin and copper mining which they smelt for tools. Mining activities intensified under colonial exploitation of the area and became a major industry since 1904. However, these minerals would be depleted within 60 years, leaving the land severely damaged. During the colonial time, Jos, the capital city of the state of Plateau, grew and became a major urban city-center with modern social amenities and infrastructures including higher educational institutions. Attracted by the opportunities in Jos and neighboring urban cities of Kano and Kaduna, many young people migrated away from Mwaghavul land in search of economic and academic prospects. Currently, most of the farmers in Mwaghavul-land are elderly people (Mutfwang, 2019).

The increasing shift away from their traditional subsistence farming and animal husbandry to a market-oriented economy has contributed to the further decline of the use of language among its people and its erosion in their everyday existence. Younger populations are socialized into the more functionally dominant languages, and their own mother tongue recedes to a language that is mainly spoken at home and is associated with grandparents and a rustic existence. Thus, the once very strong and autonomous speech community whose way of life is intertwined with their traditional place of residence and subsistence strategies is experiencing a decoupling from those factors that held them together as they become assimilated to the necessities of modern existence and acquiesce to the demands of market economy. Consequently, Mwaghavul is weakening, and diminishing in prestige and socio-cultural capital.

Marriage: Another factor influencing the vitality of Mwaghavul is marriage. As young people migrate out of the community to larger cities to prospect for education and work, they often marry exogamously. Females marrying non-native Mwaghavul invariably adopt the language of their spouses and raise their children in that language and in the language of the place of their residence. These children sometimes become heritage speaker\hearers of Mwaghavul. The males who marry non-Mwaghavul women, who still have parent\grandparents in their birthplace, and who return regularly to visit and participate in communal festivals have better chances of passing the language unto them, howbeit as L2.

The traditional forms for maintaining and continuing a language are weakening for Mwaghavul. Since colonialism, the languages of governmental institution have been English on a state and national scale, with Hausa as the dominant form of running government affairs on the local scale. Newspapers, radio, and television programming are overwhelmingly Hausa and then English. Significant is also the hostile attitude of the dominant linguistic group of the region, Hausa\Fulani, that consider autochthonous groups, divergent religious persuasion, and quest for separate identity as rebellion and resistance to their hegemonic tendencies not only to subordinate but incorporate minority peoples in the region into their sphere of influence and consequently take control of their lands for their cattle herders. The decline in traditional subsistence farming, social and economic activities enforce the continued use of these other languages, more so that educated people often migrate to larger cities and to government employments.

Religion: Although the Mwaghavul have their own indigenous religion called Kum. This religion revolves around their daily pursuits and involves divination by the yem kuum (diviner) who consults the gods, Kospa, to obtain solutions to every of the people’s needs. Currently however, 80% of their traditional religious practices, which would have aided in the sustenance of the language, has increasingly given way to Christianity. The area has been a strong focal point of proselytization by Christian missions that provide literacy, educational and social services to the people. Many young people interviewed are unaware of their people’s pre-Christian religious expressions. The 80% who are practicing Christians, mostly younger generation, conduct their services in English and Hausa. Demographically, there is a decline in the number of young speakers of the language within the community thus inhibiting traditional transmission of the language; while the number of speakers may not immediately implicate the vitality of the language, multilingualism ensures its declining role, the major threat is the proportion of its users relative to the proportion of the users of dominating high status languages of its environment and their areas of dominance in the life of the people.

Finally, Mwaghavul lacks institutional support. It is neither the language of education, religion, media nor of administration. Absent these factors that enhance the status of a language and ensure its standardization, Mwaghavul is consigned to a colloquial language for younger people, and even at that, not exclusively, due to code-switching. Traditional intergenerational transmission within the dwindling fully resident families remains the primary means of acquiring Mwaghavul as a native language, secondary transmission occurs to smaller neighboring linguistic communities such as the Bijim, Kadung, and Ngas among others through commercial contacts in the marketplace and through marital relationship. Thus, functionally, Mwaghavul is restricted to the home and market, and it is confined to informal situations. In terms of prestige, it ranks lower to English and Hausa both of which function as the languages of higher and elementary education respectively. While there is a large body of literature in English and Hausa, not so Mwaghavul, where most emerging literatures are of religious material, especially, the translation of the Bible and Christian hymns to Mwaghavul. Lacking formal governmental efforts, non-governmental and religious institutions, individuals, and scholars are leading ongoing documentation efforts, and formal study, of the language.

Media Attributions

- Screenshot 2022-11-05 182938