Livonian

LANGUAGE FEATURES

Unlike Latvian, a part of the Baltic branch of the Indo-European language family, Livonian belongs to the Finnic branch of the Uralic language family. The closest linguistic relatives of Livonian are Estonian, Finnish, and Karelian, more distant ones include Sámi, Hungarian, Mordvin, and other Uralic languages.

Although Livonian is primarily a language spoken in Latvia, Livonian language data have mainly been collected by scholars outside Latvia. The relevance of the Livonian language has long extended beyond borders and special features of this language have drawn attention on several levels. Already at the end of the 19th century, Livonian excited the broader interest of linguists of several countries. For example, it was Vilhelm Thomsen (1842–1927), a prominent Danish linguist of his time, who recognized the Livonian broken tone as being similar to a phenomenon in Danish (Thomsen 1890). The position of Livonian on the border of the Finno-Ugric and Indo-European languages and the emergence of unique language phenomena have made it interesting for researchers of different backgrounds.

Sound system and pronunciation

There are 31 letters in the modern Livonian alphabet: a ä b d ḑ e f g h i j k l ļ m n ņ o ȯ õ p r ŗ s š t ţ u v z ž. The letters c, q, w, x, y occur only in foreign names, e.g., Bach, Wiedemann, Kyrölä. The long vowel is orthographically marked with a macron above the vowel: sū ‘mouth’, lēņtš ‘southwest’, vȭrõz ‘stranger’, sīedõ ‘to eat, Inf’. The vowel length of the second syllable after a short first syllable is also marked: jõvā ‘good’, katāb ‘he/she covers’. The long consonant is denoted by writing the consonant either with one or two letters, e.g., tapāb ‘he/she kills’, ka’ggõl ‘neck’, võttõ ‘to take’. The Livonian written language is based on the East Courland dialect (e.g., Viitso 2008).

Some notes on vowels

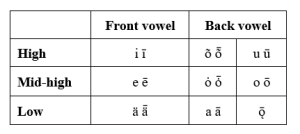

- Livonian has eight vowels: i, õ, u, e, ȯ, o, ä, a. All these vowels can be short and long. In the table, Livonian vowels are presented according to the tongue movement in the mouth:

- In East Livonian, the distinction between long mid, and low back rounded vowels ō and ǭ (no orthographic distinction!) can be made, e.g., lōda ‘table’, tǭla ‘winter’. The long mid ō is present in all Livonian dialects, it alternates with the diphthong ou, e.g. kouv ‘well’: kōvõd ‘wells’. In Central Livonian and West Livonian ā (in Estonian and in Finnish aa) serves as a counterpart to East Livonian ǭ (cf. East Livonian mǭ ‘land’ and Estonian maa ‘land’).

- Only i, a, u and a reduced vowel õ appear in non-initial syllables, e.g. vȱlda ‘to be’, kațki ‘broken’(except some foreign words, e.g., fotō ‘photo’).

- Of long vowels, ā, ē, ī and ū occur in non-initial syllables, e.g., sidām ‘heart’, kuŗē ‘devil’, kadīz ‘disappeared’, jänū ‘thirst’.

- The vowel õ is present in all Southern Finnic languages, i.e. Northern Estonian, Southern Estonian, Votic and Livonian. In the Livonian language, a distinction is made between two õ sounds: (1) õ is a high vowel, which is higher than Estonian õ, e.g., sõnā ‘word’, (b) ȯ is a mid-high vowel, which occurs only in stressed syllables following the word-initial consonants p, m, v, e.g., pȯis ‘boy’, mȯizõ ‘manor’; it is somewhat lower than Estonian õ.

- ö and ü were replaced in the whole Livonian area with e and i.

Some notes on consonants

- Livonian voiced consonants are b d ḑ g ļ ņ ŗ z ž, e.g., ažā ‘thing’, sadā ‘hundred’.

- Palatalized consonants: ḑ ļ ņ ŗ ţ, e.g., paḑā ‘pillow’, nǭļa ‘joke’, võţīm ‘key’ (palatalization is marked with a cedilla below the consonant letter).

- A long consonant is written with one letter in a word-final position and in a consonant cluster, e.g., kik ‘cock’, andõ ‘to give’.

- Fortis consonants are p t ţ k s š, e.g., sukā ‘stocking’, tappõ ‘to kill’, pūošõd ‘boys’.

- Lenis consonants b d ḑ g z ž are voiced in voiced surroundings, e.g., tabār ‘tail’, vagā ‘quiet, still’; word-finally and in front of p t ţ k s š they are generally unvoiced, e.g., rūož ‘rose’.

- There are short and long geminates, e.g., katāb ‘he/she covers’, kattõ ‘to cover’. There is a gemination of voiced plosives and fricatives, e.g., ka’ddõ ‘to disappear’, ki’vvõ ‘stone, PartSg’, i’zzõ ‘father, PartSg’.

Livonian has preserved the main prosodic features characteristic of Finnic languages, such as (a) word-initial stress and (b) the phonological opposition of short and long phoneme duration. Particular characteristics of Livonian are (a) the opposition of the plain tone and broken tone (i.e., stød), (b) the differentiation of short and long diphthongs and triphthongs, and (c) a wide difference in the structure of stressed and unstressed syllables.

Tone

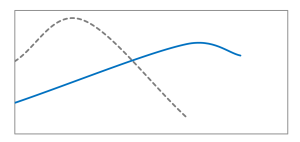

The question of tonal oppositions has been a much-debated issue in the research on Livonian prosody. In primary-stressed syllables, two tones occur: the plain (or rising) tone, and the broken tone or stød (see Figure 9), which is rising-falling or predominantly falling and is sometimes accompanied by laryngealization. The broken tone or stød also has equivalents in Salaca Livonian and South Estonian Leivu and Lutsi dialects in Latvia.

Words with broken tone or stød are usually marked with an apostrophe in transcriptions and learning materials (e.g., ki’v ‘stone’, vie’ddõ ‘to carry’). In the orthography, the broken tone is left unmarked. There is no common agreement on how to mark broken tone in IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet), but the symbol used for a glottal consonant (ʔ) is sometimes proposed.

Stress

A simplex word in Livonian usually contains one to five syllables, cf. sī ‘guilt’, pǟvaļikīzõ ‘sun, IllSg’. The word stem may be followed by an inflectional formative that may consist of a number of syllables. With the exception of a few monosyllabic words that may be unstressed in the sentence, a word has at least one stressed syllable. The primary stress is on the first syllable of a word (also in foreign words). The secondary stress is generally on the third syllable of a word.

Gradation

Livonian gradation or grade alternation consists of regular alternations of the STRONG GRADE and WEAK GRADE of stressed syllables when the word is inflected.

Weak grade Strong grade

kalād ‘fish’ (NomPl) ka’llõ ‘fish’ (PartSg)

kikīd ‘cocks’ (NomPl) kik ‘kukk’ (NomSg)

liepād ‘alders’ (NomPl) lieppõ ‘alder’ (PartSg)

kīraz ‘axe’ (NomSg) kirrõ ‘axe’ (PartSg)

võtāb ‘takes’ võttõ ‘to take’

siegūb ‘mixes’ sie’ggõ ‘to mix’

Morphology

Nouns

- Livonian, just as its Finnic relatives, does not distinguish grammatical gender for nouns or pronouns. This means that unlike in many Indo-European languages, no affixes or other particular words (such as articles) are associated with Livonian nouns, which specifically indicate the gender of the referent. Therefore, words like sõbrā ‘friend’, līvli ‘a Livonian person’, and lețli ‘a Latvian person’ can refer to either a male or female individual. However, there are nouns in Livonian, which inherently distinguish gender just by virtue of the information within the word itself, e.g., nai ‘woman; wife’ vs. mīez ‘man; husband’, kēņig ‘king’ vs. kēņigjemānd ‘queen’; kanā ‘hen’ vs. kik ‘rooster’.

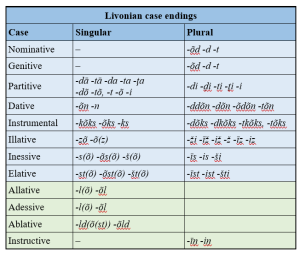

- Livonian is typical of other Finnic languages in that it has a large number of noun cases. The dictionary by Viitso & Ernštreits (2012) gives as many as 17 noun cases for Livonian. The standard inventory of nominal cases contains 8 productive (highlighted in light blue in the table) and 4–5 unproductive cases (highlighted in light green in the table). Nouns inflect for case and number.

- The nominative and the genitive singular and plural forms are mostly homonymic, e.g., kalā : kalā ‘fish’, kalād : kalād ‘fishes’, lēba : lēba ‘bread’, lēbad : lēbad ‘breads’. There are exceptions in several instances, e.g., nai : naiz ‘woman’, kuolmõz : kuolmõnd ‘third’, läpš : laps ‘child’, kēļ : kīel ‘language’, täm : tam ‘oak’.

- Differently from Estonian which uses exterior cases to express recipient, possessor, etc., Livonian uses the dative case (cf. Mordvin and Baltic languages), e.g., Mi’nnõn vȯ’ļ i’bbi ‘I had a horse’, Jǭņ tȭitiz Pētõrõn ī’d lambõ ‘Jǭņ promised Pētõr one sheep’. However, the elative occurs as well, e.g., Ta vȯtšūb mi’nstõ a’bbõ ‘He/she is looking for help from me’. The dative also marks the experiencer, e.g., Tä’mmõn um kīlma ‘He/she is cold’.

- Possessive genitive and dative are both used to express whom sth belongs to or part of which sth is, e.g., Se um mi’n pūoga ‘This is my son.’, Se mǭ um mä’ddõn ‘This land is ours.’

- In addition to expressing the atelicity of a subject or an object, the partitive case expresses a separate part of a whole or an entity in certain phrases, e.g., in kabāl leibõ ‘piece of bread’ where leib-õ is the partitive of lēba ‘bread’.

- Instead of the translative and the comitative cases present in other Finnic languages, in Livonian there is the instrumental case (like in Baltic languages), e.g., kīelkõks ‘with a tongue’. The translative and comitative functions can be separated only rarely, cf. piʼņ/kõks ‘with a dog’ and piʼņņ/õks ‘(turn) into a dog’ – Se kutški kazāb sūr pi’ņņõks ‘This puppy will turn into a big dog’ and Ma lǟ’b pi’ņkõks kenžlõm ‘I’m going for a walk with the dog’.

- The cases called allative, adessive and ablative are used with certain place names (e.g., Livonian villages Irē, Sīkrõg, Kuostrõg, etc. > Irēl ‘in or to Irē’, Sīkrõgõld ‘from Sīkrõg’, Kuoštrõgõl ‘in or to Kuoštrõg’), they appear in certain phrases, adverbials, e.g., lovāl ‘in bed’, aʼbbõl ‘(go for) help’, sīel āigal ‘at that time’.

- The instructive case denotes the way an action is carried out, e.g., jālgiņ ‘on foot’, but most often it refers to measures and other units that say how something moves, is measured, etc. (sumāriņ ‘piece by piece, stūndiņ ‘for hours).

- There are some lexicalized instances of the essive, for instance, some adverbials expressing a) time, e.g. ȭ’dõn ‘in the evening’, brēḑõn ‘on Friday’, tu’lbiz āigastõn ‘next year’, b) place, e.g. kuo’nnõ ‘at home’, c) and state, e.g. opātijizõn ‘as a teacher’, contain traces of the essive.

Due to the large variation in case endings and also variation within particular cases, Livonian nouns are grouped into several hundred declension types. Each type describes the exact way nouns in that group are declined for all cases and each group is assigned a unique numerical index, which appears in dictionaries alongside each noun. The most comprehensive and extensive description of Livonian declension types can be found in Viitso & Ernštreits 2012 and the dictionary’s online versions.

Pronouns, question words, adpositions

Livonian pronouns:

Singular Plural

minā, ma ‘I’ mēg (meg) ‘we’

sinā, sa ‘you’ tēg (teg) ‘you’

tämā, ta ‘he/she’ nämād, ne ‘they’

No gender distinction exists for third-person pronouns in Livonian. Therefore, the singular forms (tämā, ta) are equivalent to ‘she’ or ‘he’. Similarly, the plural form (ne) is equally applicable to groups of third-person referents regardless of gender. Livonian personal pronouns are declined according to the case.

Question words are also declined according to the case. In Livonian, as in other Finnic languages, there are two series of question words differentiated by animacy. Question words derived from kis are used for living beings and those derived from mis are used for inanimate objects. This is roughly the same as the distinction in English between who and what.

There are both postpositions and prepositions in Livonian. Many locative postpositions have three forms corresponding to the three-way distinction (towards/in/from) present in the locative noun cases. For example, alā ‘downward’, allõ ‘under’, aldõst ‘from underneath’. Postpositions such as these can also function as adverbs lending a perfective meaning to the verbs they occur with and also coloring their meaning. (e.g., kēratõ ‘to write’ vs. alā kēratõ ‘to sign’) Some examples of postpositions include allõ ‘under’ (tam allõ ‘under the oak tree’), jūs ‘by at’ (sõbrā jūs ‘by/at the friend), pǟl ‘on’ (vie’d pǟl ‘on the water’), sizāl ‘inside’ (kougõl sizāl ‘inside the bread mixing bowl’), sōņõ ‘until, up to’ (jo’ug sōņõ ‘up to the river’). Examples of prepositions are for example i’ļ ‘about’ (i’ļ sīe ‘about it’) and pi’ds ‘along’ (pi’ds riekkõ ‘along the road’). All of the postpositions and prepositions in these examples take nouns in the genitive case. However, there are other adpositions, which take nouns in other cases (for example in partitive or instrumental).

Verbs

Finite forms inflect for person, tense, mood, polarity, and number. Livonian has two tenses,

- – present (e.g., Izā lugūb rǭntõzt ‘Father is reading a book’)

- – past (e.g., Izā lugīz rǭntõzt ‘Father was reading a book’),

and five moods,

- – indicative,

- – conditional (e.g., Vȯlks ni mi’nnõn rǭz võita, ma tīeks vȭidagstleibõ, bet leibõ ä’b ūo. ‘If I had some butter, I would make a sandwich, but there is no bread.’),

- – imperative (e.g., Rõkānd vizāstiz ja lougõ! ‘Speak loudly and slowly!’),

- – quotative (e.g., Tä’mmõn vȯ’lli ūž ja interesant rō̜ntõz, kīenda ta tǭ’ji mi’nnõn nä’gt̜õ. ‘S/he is said to have a new and an interesting book that s/he apparently wants to show me.’),

- – jussive (e.g., La’z võtāg sīe ibīz ja pangõ rattõd je’ddõ ‘Let him/her take the horse and put it in front of the horsecart.’).

As in the other Finnic languages, verbs in Livonian are negated using a special negative verb used in conjunction with a root form of the lexical verb (in the present and past tense):

- – affirmative (e.g., Ma opūb līvõ kīeldõ. ‘I learn Livonian’, Ta tulks tǟnõ. ’S/he would come here’),

- – negative (e.g., Ma ä’b op līvõ kīeldõ. ‘I don’t learn Livonian’, Ma i’z op līvõ kīeldõ. ‘I didn’t learn Livonian’, Ta ä’b tulks tǟnõ. ‘S/he would not come here’).

To express future time, Livonian generally uses a verb in the present tense, e.g. Mūpõ ma tulāb o’bbõ kuodāj ‘Tomorrow I will come home late’. The future interpretation becomes clear from the broader context, in this case from the future adverbial mūpõ ‘tomorrow’. In addition, līdõ ‘will be’ as a future auxiliary is used, e.g. Pūogast līb kalāmīez ‘The son will become a fisherman’.

Media Attributions

- Picture22

- Screenshot 2023-05-26 095242

- Picture23

- Screenshot 2023-05-26 095336