Ekegusii

Language Features

Ekegusii sound system:

The sound system of Ekegusii can be analyzed from the segmental and suprasegmental perspectives. A segmental description of consonants, vowels (monophthongs, diphthongs, and triphthongs), and suprasegmentals, that is, tone, and syllable structure will be discussed here.

3.1. Ekegusii Vowel system

Ekegusii has seven vowel phonemes (for a deeper acoustic discussion on Ekegusii vowels see Otieno & Mecha, 2019) with a length distinction. That is, for every vowel phoneme, there is a corresponding long vowel counterpart. These vowels are /i e ɛ a ɔ o u /. The vowels are evenly distributed between the front and back distinction, that is, three front vowels /i e ɛ/, three back vowels /ɔ o u/, and one low, central vowel /a/.

3.1.1. Front vowels

These vowels are articulated with the tongue positioned as far forward as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction.

[i] a close front vowel

[e] a close-mid front vowel

[ɛ] an open-mid front vowel

The vowels above are in the following words.

Vowel Standard orthography Transcription Gloss

[i] ita /ita/ kill

[e] eta /eta/ pass

[ɛ] ega /ɛɣa/ seduce

3.1.2. Central vowel

Ekegusii language has only one central vowel [a]. in its articulation, the tongue is positioned halfway between a front and a back vowel. Here are examples of the vowel /a/.

Vowel Standard orthography Transcription Gloss

[a] ata /ata/ break

[a] aka /aka/ paint

3.1.3. Back vowels

Ekegusii back vowels are articulated with the tongue positioned far back in the mouth without creating any constriction as pertains to vowel production. There are three back vowels in the language.

[u] a close back vowel

[o] a close-mid back vowel

[ɔ] an open-mid back vowel

These are captured in the following examples:

Vowel Standard orthography Transcription Gloss

[u] uba /uꞵa/ reach a dead end

[o] oga /oɣa/ make noise

[ɔ] oma /ɔma/ smear (mud)

The seven vowels in Ekegusii occur both as short and long vowels (see Otieno, Mecha, and Opande, 2020). Omwansa, (2021) proposes that the central vowels in Ekegusii are [a] and [ɑ] but considering their acoustic qualities, I conclude that the variations he observed were just effects of neighbouring sounds. He did not carry out acoustic experiments for the sounds in citation form and compared the results with those in running speech.

The vowel phonemes and their length distinctions are illustrated below:

Orthography transcription gloss

rina ɾina refuse (to give something)

riina ɾi:na climb

bera ꞵeɾa boil

beera ꞵe:ɾa get angry with someone/something

era ɛɾa get finished

era ɛ:ɾa five-cent coin

baka ꞵaka go astray

baaka ꞵa:ka praise (someone/something)

soka sɔka pack

sooka sɔ:ka get out/married

goka ɣoka come to pieces/unhafted

gooka ɣo:ka rejoice

buta ꞵuta dismiss/sack/fire from work

buuta ꞵu:ta tarry/linger

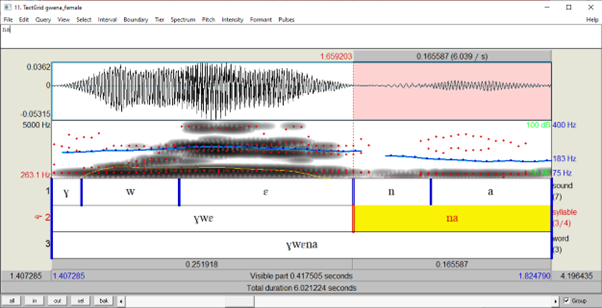

Otieno, (2020) looked at these qualities of vowels comparing productions as produced by informants from the two dialects of Ekegusii. In general, males have glottal vibration, that is, fundamental frequency that is considerably lower than that of females. This finding agrees with Ladefoged (2001a) that adult males have a fundamental frequency of 80-200 Hz whereas females have up to 400 Hz of fundamental frequency (F0). The F0 for children goes up to 500 Hz (Liberman 1977). This is because of the greater mass, length, and tension of the vocal folds. Men have long and massive vocal folds whereas females and children have shorter and less massive vocal folds. Smaller and less massive vocal cords are associated with a faster vibration of the vocal cords (Clark & Yallop 1995). These findings are a pointer to the variations that result from the sex and age of Ekegusii speakers.

3.1.4. Diphthongs

Ekegusii diphthongs occur at the beginning, center, or end of a word. These sequences of vowels are very productive in Ekegusii as so many words have these sounds as seen in the examples below.

Diphthong Standard orthography Transcription Gloss

[ae] baete /ꞵaete/ (they) pass

[aɛ] bae /ꞵaɛ/ (they) give

[ai] kai /kai/ where

[ao] kwao /kwao/ yours (land)

[aɔ] maoto /maɔtɔ/ name of a person

[au] mauti /mauti/ name of a person

[ea] eanga /eaŋa/ cloth

[ei] egeitano /eɣeitanɔ/ strife/conflict

[eo] ekeonga /ekeoŋa/ fish trap

[eu] eura /euɾa/ undigested stomach contents

[ɛɔ] eome /ɛɔmɛ/ smear oneself

[ia] tiana /tiana/ swear

[ie] tiema /tiena/ leap playfully

[iɛ] tiera /tiɛɾa/ eat huge food quickly

[io] sioka /sioka/ appear suddenly

[iɔ] eriogo /eriɔɣɔ/ medicine

[iu] riuro /ɾiuɾo/ foam

[oa] goaka /ɣoaka/ to beat

[ɔa] soa /sa/ enter

[oe] moeti /moeti/ make him/her pass

[ɔɛ] toe /tɔɛ/ give us

[oi] oigo /oiɣo/ name of a person

[ɔi] boigo /ꞵɔiɣɔ/ also

[ou] bouti /ꞵouti/ name of a place

[ua] buati /ꞵuati/ follow

[ue] tuera /tueɾa/ spit on

[uɛ] suebeka /suɛꞵɛka/ become less swollen

[uo] tuoma /tuoma/ hit

[uɔ] etuoni /etuɔni/ cock/roaster

3.1.5. Triphthongs

Ekegusii has a combination of vowels gliding from one vowel to another and then to a third vowel produced rapidly without interruption. A few vowels appear as triphthongs, unlike the highly productive diphthongs.

Triphthong Standard orthography Transcription Gloss

[aei] baeire /ꞵaeire/ they have given

[iai] giaito /ɣiaito/ ours

[iao] ekiao /ekiao/ yours

It is worth noting that some triphthongs could result from a combination of a prefixed vowel combining with those of a root word. Care was taken, for the examples above, to exclude such words as they will not be a true reflection.

3.1.6. Elision in Ekegusii

Most words in Ekegusii begin and end with vowels. It is a normal speech act for speakers of the language to leave out part of a word when one is pronouncing it. This is frequent and increases in rapid connected speech.

Ekegusii words Elision Gloss

Taiyo igaa taiyaa he/she is not here

Taracha aiga tarachaa he/has not come here

Tarakwana boigo tarakwanabo he/she has not said so

Esese embe sesembe a bad dog

Aiga inse insaa down here

Elision in the language occurs in such a manner that when two vowels are separated by word or morpheme boundaries, the first vowel is dropped as below:

Omoyo one – omoy’one (my heart)

Riote eri – riot’eri (this wound)

This is not always the case as seen in the examples above where word or morpheme boundaries are not the core criteria for ellipsis.

3.2. Ekegusii consonant system

In this section, I will present the segmental phonology of Ekegusii consonants and the phonological rules that they operate in. Some work has been done on this by Cammenga, (2002), Mecha, (2006), and Otieno and Mecha, (2019).

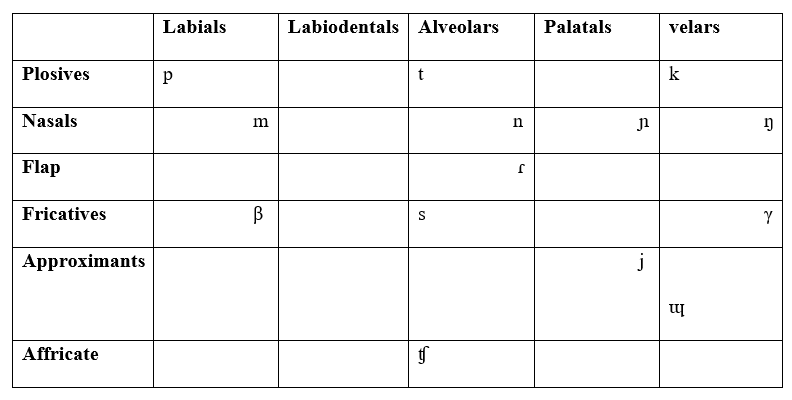

The earliest work on the Ekegusii sound system by Whiteley (1965:3) identifies Ekegusii consonants as follows: [β γ m n ʧ ŋ ɲ ɾ s t j ɰ k p], a total of fourteen. The IPA chart of Ekegusii would then look as seen below:

According to Omoke (2012), the consonant IPA Chart does not include the nasal compounds or the clusters of the glide [ɰ] as shown above.

Nash, (2011) includes [b d g w] into the Ekegusii consonant inventory at the phonetic level. He conjectures that they are allophones or marginal segments. I assert that these sounds are borrowed having come into common use with the borrowed lexical items. Except for [p] which has few examples, the rest are a result of language contact with neighbouring languages like Dholuo, Maasai, Kipsigis, and the official languages of Kiswahili and English. Many of the borrowed sounds have been entrenched into the working sound system of the language as further evidence of sound change or language shift already underway in the language.

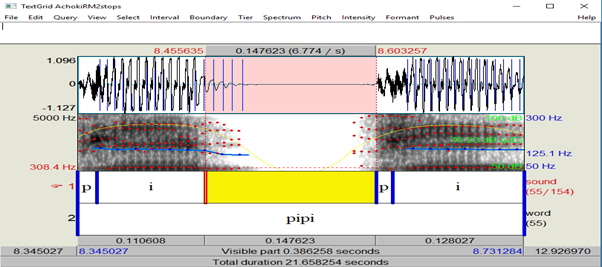

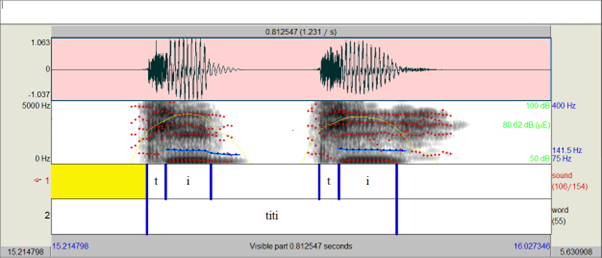

3.2.1. Stops

Otieno, (2020) says that Ekegusii has three stop consonants [p t k] unlike Nash, (2011) who presented only two, [t k]. These sounds do not have their voiced counterparts. Otieno, 2020 gives a detailed acoustic and impressionistic description of the three sounds.

The above waveforms and spectrograms display the acoustic characteristics of Ekegusii stop consonants annotated using Praat. As indicated early, /p/ is not very productive as are other voiceless stop consonants /t k/. Notice that Ekegusii does not have voiced stop consonants.

3.2.2. Nasals

From the chart above you will notice that nasals in Ekegusii are /m n ŋ ɲ/. This class of sounds is highly productive as we find we find many other consonants being pre-nasalized as we shall see in sections below. The phonemic status of the four nasals is exemplified in the minimal pairs given below.

Transcription Gloss Transcription Gloss

/kuma/ be famous /kuna/ touch

/ama/ grow (plant) /ana/ bellow/bleat

/kuɲa/ dig /kuŋa/ accumulate/keep

/ɲɔkɔ/ your mother /ŋɔkɔ/ name of a person/hen

3.2.3. Fricatives

There are three fricatives in the Ekegusii language: bilabial /ꞵ/, alveolar /s/, and velar /ɣ/. The following minimal pairs exemplify their phonemic status.

Transcription Gloss Transcription Gloss

/ꞵi:ta/ ready to attack /si:ta/ hesitate

/ɣa:ta/ position to attack /sa:ta/ decorate/beautify

/siɾi/ lose /ꞵiɾi/ eat (them)

/sɔa/ enter /ꞵɔa/ tie

/ɣoɾa/ buy /boɾa/ disappear

3.2.4. Affricate

Ekegusii has a single voiceless palatal affricate [ʧ] as in:

Ekegusii orthography IPA symbol Example Transcription Gloss

CH,ch ʧ choka / ʧoka/ forage

chaka /ʧaka/ start

gacha /ɣaʧa/ keep

achachi /aʧaʧi/ frequent

chori /ʧɔɾi/ abuse

3.2.5. Flap

The language has one flap an alveolar /ɾ/. It is a very productive sound in the language.

Transcription Gloss

/ɾoma/ bite

/ɾɛɾɔ/ today

3.2.6. Approximants

Ekegusii has two approximants, labial-velar approximant /w/ and palatal approximant /j/. /w/ is not productive since it usually appears in idiophones in words expressing surprise. It only appears in free variation depending on whether one speaks Ekerogoro or Ekemaate Dialect of Ekegusii (Otieno, 2020). Fig. 4 below shows a waveform and spectrogram of /ɣwɛna/.

In all instances where segment /w/ appears, it has to be in a C_V environment (Nash, 2011). This makes it to be a peripheral consonant and more so, it comes in free variation with the vowel sequence of /ua/ or /uɔ/as in:

Transcription Gloss

/kwani/ or /kuani/ greet

/mwoni/ or /muoni/ (you) sell

As seen above, the labio-velar approximant happens on the surface since the morphemic characterization is as thus:

Mu – ɔ – ni

2P Pl- you – sell

For the speakers of the Ekerogoro dialect, the mu is realized as mw- in all instances of this combination. This sound always comes in free variation with diphthong combination of /ue/, /uɛ/, /uɔ/, /ua/ and /oe/ as a consequence of coarticulation in running speech.

The labio-velar approximant [w] in Ekegusii is disputed or even eliminated as in Nash, (2011) since we cannot have a minimal pair with it and also by it only co-occurring with other sounds in a cluster as shown below:

Ekegusii orthography IPA symbol Example Transcription Gloss

BW βw bwone / βwͻnɛ/ my place

CHW,chw ʧw chweya /ʧwɛja/ walk

GW,gw ɤw gwena /ɣwɛna/ get well

KW,kw kw kwana / kwana/ say

MW,mw mw mwao /mwao/ your house

NYW,nyw ɲw kanywe /kaɲwe/ drink

SW,sw sw enswe /enswe/ fish

NW,nw nw inwe /inwe/ you (pl.)

TW,tw tw twara /twa:ɾa/ hunt

NGW,ngw ŋw ngwani /ŋwani/ whip/lash

I take the view that /w/ cannot be a consonant in the sound system of Ekegusii for two reasons: one, as it is not contrastive and hence not phonemic; two, it arises from the underlying /u/ in many instances; and three, can be a result of Mid-Vowel Raising (Cammenga, 2002) as in the examples below.

enoɾa + nominal prefix (o-mo-) ——– o-mo-enoɾa – omwenoɾa/ omuenora

The sound /j/ is very productive and contrastive in the language. Minimal pairs establish their phonemic status as seen below.

Orthography pronunciation gloss

yacha /jaʧa/ it came

bacha /ꞵaʧa/ they came

twacha /twaʧa/ we came

In a language that is currently experiencing ongoing sound changes, younger speakers of the language have been noted to produce /w/ instead of /ɣw/ as it appears in the traditional C_V environment as noted earlier.

3.2.7. Orthography

The orthography of consonants (and of vowels) as represented in the language is as follows:

Ekegusii orthography IPA symbol Example Transcription Gloss

B,b β baba /βaβa/ mother

G,g γ gaki / γaki/ please

K,k k kaana /ka:na/ deny

M,m m amate /amate/ saliva

N,n n enogo /enoγo/ fool

P,p p pi /pi/ completely

R,r ɾ riina / ɾi:na/ climb

S,s s sata /sata/ decorate

T,t t tota /tota/ become soft

Y,y j yee /jɛ:/ give it

W,w w rigwari / ɾiγwaɾi/ zebra

NY,ny ɲ enyanya /eɲaɲa/ tomato

NG,ng ŋ engiti /eŋgiti/ beast

Whitely (1965:4) also says that some consonants in Ekegusii occur as nasal compounds. This class of consonants is very productive in the language as many words are readily available as examples:

orthography IPA symbol Example Transcription Gloss

MB,mb mb kemba /kemba/ waylay

ND,nd nd enda /enda/ stomach

NK,nk ŋk inko /iŋkͻ/ give way

NCH,nch nʧ inchu /inʧu/ come

NG,ng ŋg ningo /niŋgo/ who

3.3. Suprasegmental features

Ladefoged and Johnson (2011:187) say that speech sounds differ in pitch, in loudness, and quality. Especially, the quality of a sound depends on its overtone structure. They argue that various overtone pitches give sounds their distinctive quality. The various speech sounds can be distinguished by the differences in these overtones or formants. The lowest three formants distinguish vowels from each other. In this work, I will consider the syllable structure of Ekegusii and tone.

3.3.1. Ekegusii syllable structure

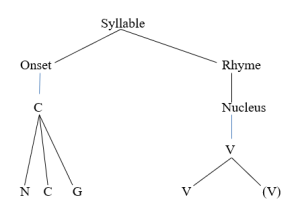

Languages differ significantly in their syllable structure. The basic architecture of a syllable as in Goldsmith (1990) which is shown below is modified to fit the language phonotactics of Ekegusii.

The above diagram can be contextualized in Ekegusii to cut out the coda and maximize the onset.

There are indeed many phonological processes which are activated at the syllable level. One such is tone – Ekegusii being a tone language. As Blevins (1996) aptly quips, “such rules and constraints are sensitive to a domain that is larger than the segment, smaller than the word, and contains exactly one sonority peak.”

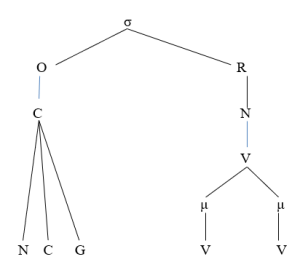

The basic syllable in Ekegusii is made up of a vowel segment preceded by zero or more consonantal segment. Like all languages, the nucleus in Ekegusii is a vowel – the peak of a syllable. This can be represented as:

From the above schema, notice that the nucleus is an obligatory element in every Ekegusii syllable and it marks the end of the syllable. It contains a short vowel, a long vowel, or a combination of vowels. The nucleus must also contain a minimum of one Mora (μ) and at most two moras.

Ekegusii rhyme does not branch. Codas are not possible in the language (Nash, 2011). Ekegusii does not have a coda after the nucleus since every syllable ends in a vowel. For the two constituents, the nucleus is obligatory while the onset is optional. When in other languages like English the nucleus must not be always a vowel (Davenport and Hannahs 2005), in Ekegusii the nucleus must be a vowel.

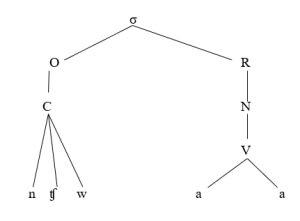

Onsets of Ekegusii syllables have several possible permutations as seen in Nash, (2011) which is extended in this work to be three from two according to Nash. They are a single consonant, prenasalized consonant, consonant glide, prenasalized consonant, and glide. Therefore, a maximal Ekegusii syllable can be represented in a tree diagram for the word nchaa /nʧwa:/ ‘come here’ as:

The above tree diagram demonstrates that we can have up to three consonants in the onset. The rhyme is not branching as noted above but can have as many vowels as three as in the following schema for the word kiao /ekiao/ ‘your thing’

The above syllable has a maximal V branching of the nucleus as a triphthong.

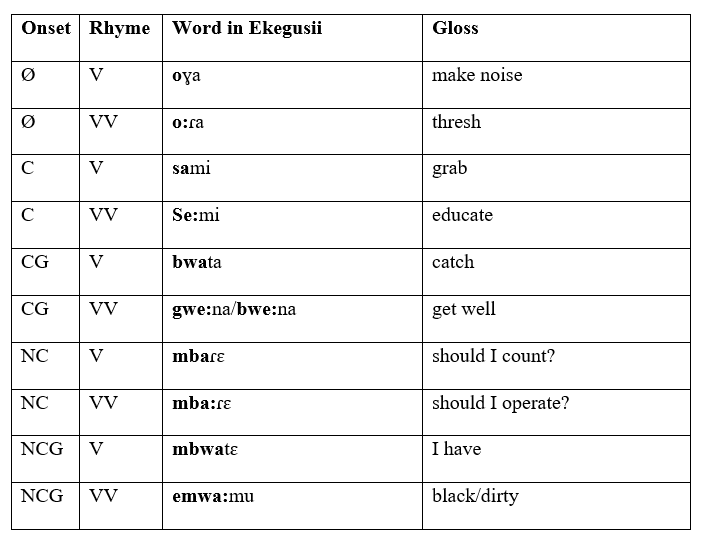

I agree with Nash, (2011) who says that the only possible onsets in Ekegusii are: (1) Ø, (2) C, (3) NC, (4) CG, and (5) NCG. This is demonstrated in the following table.

This research disputes Nash, (2011) assertion of some distributional restrictions on some syllable shapes. Especially noted, syllables with long vowels are not prohibited in word-final positions as otherwise noted by Nash. The following are examples:

Transcription Gloss Transcription Gloss

/ta:/ pour out liquid /kaɾwa:/ go away from here

/keɾa:/ male name /moɾa:/ female name

/oɾoe:/ slap /eʧi:/ diarrhoea

These are counterexamples to Nash’s, (2011) observation that long vowels are prohibited in word-final positions. This formation is nonetheless not very productive. One thing still stands out: long vowels are attested at word initial, word medial, and word-final positions.

3.3.2 .Sonority in Ekegusii

Davenport and Hannahs (2005:75) say that every speech has a degree of sonority determined by factors like the loudness concerning other sounds, the extent to which it can be prolonged, and the degree of stricture in the vocal tract. They say that the more sonorous a sound, the louder, more sustainable, and more open is. They point out that voiced sounds are more sonorous than voiceless ones.

In acoustic terms, sonority is related to formant patterns; the more sonorant a sound, the clearer, more distinct its formant structure. Speech sounds in Ekegusii can be arranged on a sonority scale as:

Least sonorant voiceless stops /p t k/

Affricate /ʧ/

Voiceless fricatives /ꞵ s ɣ/

Nasals /m n ɲ ŋ/

Glides /j w/

High vowels /i u/

Mid-high vowels /e o/

Mid-low vowels /ɛ ɔ/

Most sonorant low vowel /a/

The scale has an important role to play in determining the selection of the nucleus of a syllable and the order of segments within the onset and the coda. The general principle is that the most sonorous sounds are selected as syllabic nuclei with sonority increasing within the onset. The nucleus is the high point of sonority or peak.

3.3.3. TONE in Ekegusii

Ekegusii is a tone language – a language that uses pitch variations as a means of creating lexical contrast (Yip, 2002; Hyman, 1975). Ekegusii is seen to employ tone to distinguish word meanings or to convey grammatical distinctions. The tone in Ekegusii serves to mark different verb tenses, possession, negation, and nominal categories. In this way, the meanings of the same phonemic segments, in the same arrangement, are distinguished by the pitch patterns as in the following example.

Transcription Gloss Transcription Gloss

/mˋoʹake/ beat him/her /mˋoˋake/ go away

Tonal variations in Ekegusii are used to distinguish dialectal identities between speakers of Ekerogoro and Ekemaate dialects.

Hyman, (1975) suggests that in a tone language, both pitch phonemes and segmental phonemes enter into a composition of at least some morphemes. We thus observe as in the above examples the segments are alike yet pitch variation sets the two lexical items apart. In Autosegmental phonology (AP) Goldsmith, (1990) gives a way of describing the segments as tone-bearing units.

There are three tone patterns in Ekegusii: High (H), Low (L), and Falling. Nash, (2011) points out that falling tone is only found on long vowels, hence not contrastive in the language just like H and L tones. We can therefore assume that the falling tone is a kind of movement from H to L in a concatenation.

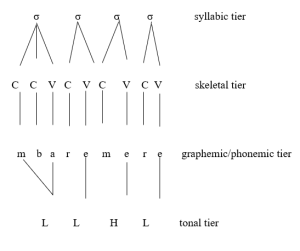

Autosegmental Phonology (AP) as clearly articulated by Goldsmith (1976), handles autonomous articulatory parameters like tone, voicing, aspiration, and nasalization, which are, in principle, independent. This is also called Non-linear phonology. As regards tone, it simplifies the representation and allows it to be given an autonomous representation on a separate tier in AP. There is no one-to-one relationship between the number of tones and vowels. One vowel can be associated with many tones and vice versa (Kenstowicz, 1994; Odden, 2005). Durand (1990:242) observes that the anchoring device in the entire phonological representation is the skeletal tier, also called the CV tier, which forms the anchor point for elements on the other tiers.

Below is a sample function of AP showing the relationship between the tiers using the Ekegusii word mbaremere ‘I will dig for them.’

This is the most common form of tonal representation apart from the other forms discussed later here. The diagrammatic representation makes a chart which is a pair of tiers along with the set of association lines that mediate them.

The following are the major principles of Autosegmental Phonology as described by Massamba (1996) and Snider (1999), which include the multilinear representation of segments, the association convention, the well-formedness condition (WFC), and the obligatory contour principle (OCP).

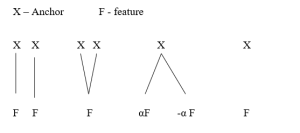

In the multilinear representation, segments and autosegments belong to different levels (tiers). This forms the basis on which Autosegmental phonology is also referred to as multilinear or non-linear phonology since it outgrows the linear ordering of SPE. As Kenstowicz (1994:311) explains, non-linear phonology drops the idea of a one-to-one relationship in phonological representation. Non-linearity, therefore, allows for all such representations:

The association convention is described as a mental schema used to show a surface representation of the relationship between the tiers (Massamba, 1996:176, Snider, 1999:7). To illustrate the principle Goldsmith (1990) shows that each morpheme contributes a tone to the tone melody of the word. This applies to Ekegusii. That is, there is the same number of tones and vowels in the language since segmental tone assignment in the language is in such a manner that every vowel (mora) is a tone-bearing unit (TBU). The following diagrammatic representation illustrates the concept:

In the convention, unbroken lines (as above) are used to indicate relationships that already exist. Part of a structural change is indicated by a dashed line, while a line deleted by a rule is indicated by an X or Z cutting through the line. The High tone shift diagram below summarizes the latter three concepts.

The third major principle of Autosegmental phonology is the Well Formedness Condition (WFC), which enables the lines to perform their correct role and states as follows:

a) Each vowel must be associated with at least one tone.

b) Each tone must be associated with at least one vowel.

c) No association lines may cross.

(Katamba, 1989:203)

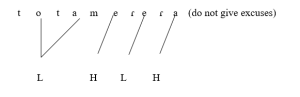

An example of the infinitival word ‘ogotamera’ (place of refuge) can be used to illustrate the well-formedness principle.

Snider (1999:08) states the obligatory contour principle as follows: ‘Adjacent identical features are prohibited on the same tier’. Fox (2000:224) clarifies this principle thus: It is assumed that identical tones in a sequence constitute a single occurrence of a tone on the tonal tier; sequences of like tones on this tier are not permitted. For instance, the HHL sequence simplifies to HL. A tone, therefore, spreads to another to make it look like two similar tones are adjacent.

Media Attributions

- Table 1

- Picture2

- 4

- 5

- 6

- Screenshot 2022-11-05 154451

- Screenshot 2022-11-05 154703

- Screenshot 2022-11-05 154933

- Screenshot 2022-11-05 155129

- Screenshot 2022-11-05 155317

- Screenshot 2022-11-05 155527

- Screenshot 2022-11-05 155839

- Screenshot 2022-11-05 160041

- Screenshot 2022-11-05 160302

- Screenshot 2022-11-05 160426

- Screenshot 2022-11-05 160834